Bird brains: what they can tell us about ecology and evolution

For my inaugural post here at The Integrative Paleontologists, I am going to discuss a recent paper in PLOS ONE that highlights some of the aspects I love most about being a comparative biologist.

Paleoecology is the area of paleontology I am most interested in–and now, many paleontologists are spending a significant portion of their time examining extant species in order to understand more about the features and signals found in the fossil record. Fossils are often fascinating morphologically but information such as behavior and ecology can be difficult to access in long-dead specimens with no soft tissue preservation and of course, no live observations. We as paleontologists need to think of creative comparative methods that can breathe some life back into old bones.

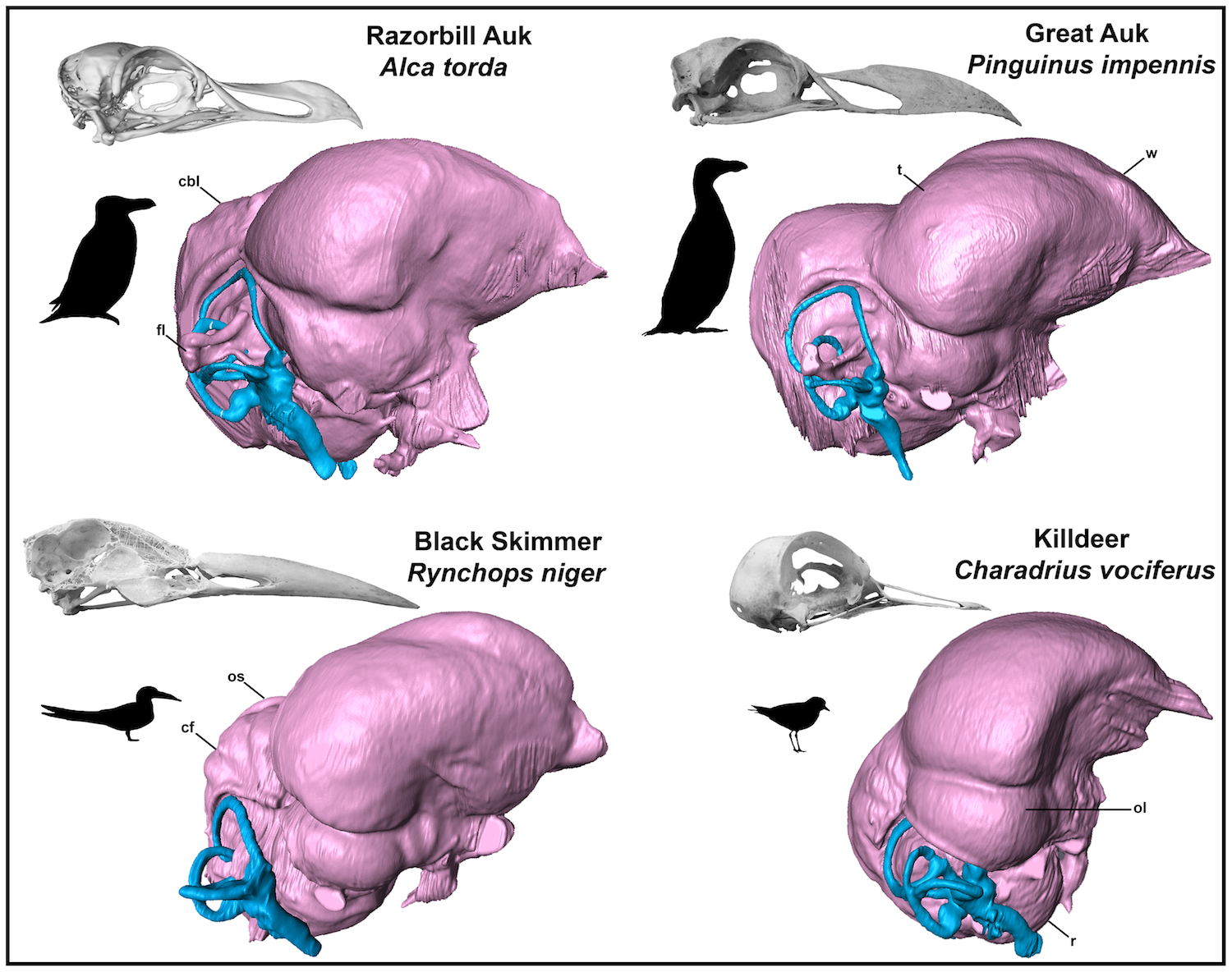

In their recent paper, Adam Smith and Julia Clarke use high resolution CT scanning to look at a variety of structures in the endocranial region of a group of birds called Charadriiformes (plovers, sandpipers, gulls, terns, and their allies). Within charadriiforms, a wide variety of locomotor and feeding ecologies are represented–ranging from auks, which are wing-propelled divers, to marsh sandpipers, which are terrestrial ground-foragers.

Morphology preserved in the brain case of vertebrates can correspond to certain unique ecologies and life histories. Charadriiformes are a good group to test this on because of their diverse ecologies and well-known evolutionary relationships. I will highlight a few of their findings here:

- The “wulst”, also known as the sagittal eminence, is a structure in the brain of birds linked to sensory and visual perception. This structure can be reconstructed using a digital endocast. Interestingly, the only two terrestrially foraging species sampled possess a uniquely positioned wulst when compared to the other charadriiforms. On the other hand, both flightless and volant species possess similarly shaped wulsts so it may not be useful in predicting flight styles of birds.

- The inner ear is comprised of a bony tube, known as a labyrinth. The characteristics of this labyrinth have been known to accurately predict how acrobatically an animal can move. Although in this group of birds, it appears that labyrinth shape and structure is conserved, even between divers and non-divers.

Cranial endocasts of four species in this study illustrating differences in endocranial morphology. Smith and Clarke 2012 (CC-BY)

- Overall, it was shown that flightless wing-propelled divers have relatively smaller brains for their body masses and also smaller optic lobes than volant members of the same group. There was one species, the Black Skimmer (Rynchops niger) that was strikingly different from all of the others that were sampled. The Black Skimmer has, among other unique endocranial characteristics, an unusually large wulst. This seems to be related to the Black Skimmer’s unique tactile feeding ecology– it feeds at the surface of the water by skimming the surface with its lower jaw (video from YouTube here).

Learning the details of these endocranial morphological correlates to behavior and ecology is invaluable to understanding the endocranial characters we see in fossils. Charadriiforms have a robust fossil record; so fossil specimens from this group can be CT scanned in order to enlighten us as to potential feeding and behavioral traits now that the significance of these morphological features are known. I think increasingly paleontologists will turn to studying extant species with new advanced technologies that we can also apply to our fossil specimens, allowing us to better grasp ecology in deep time. Expect to hear more on this topic from me in the future!

Citation:

Smith NA, Clarke JA (2012). Endocranial Anatomy of the Charadriiformes: Sensory System Variation and the Evolution of Wing-Propelled Diving. PLoS ONE 7(11): e49584. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049584