Fossil Egg-cellence

I’m usually thinking about eggs. Not chocolate eggs (well, maybe this time of year), but fossil eggs. I am really interested in fossil eggs and what they tell us about behavior, but also the environments they were laid in. I have written before about stable isotopes, which can be used in egg and eggshell studies, but I will begin more generally about fossilized eggs and why so many paleontologists are keen to crack their mysteries (see what I did there?)

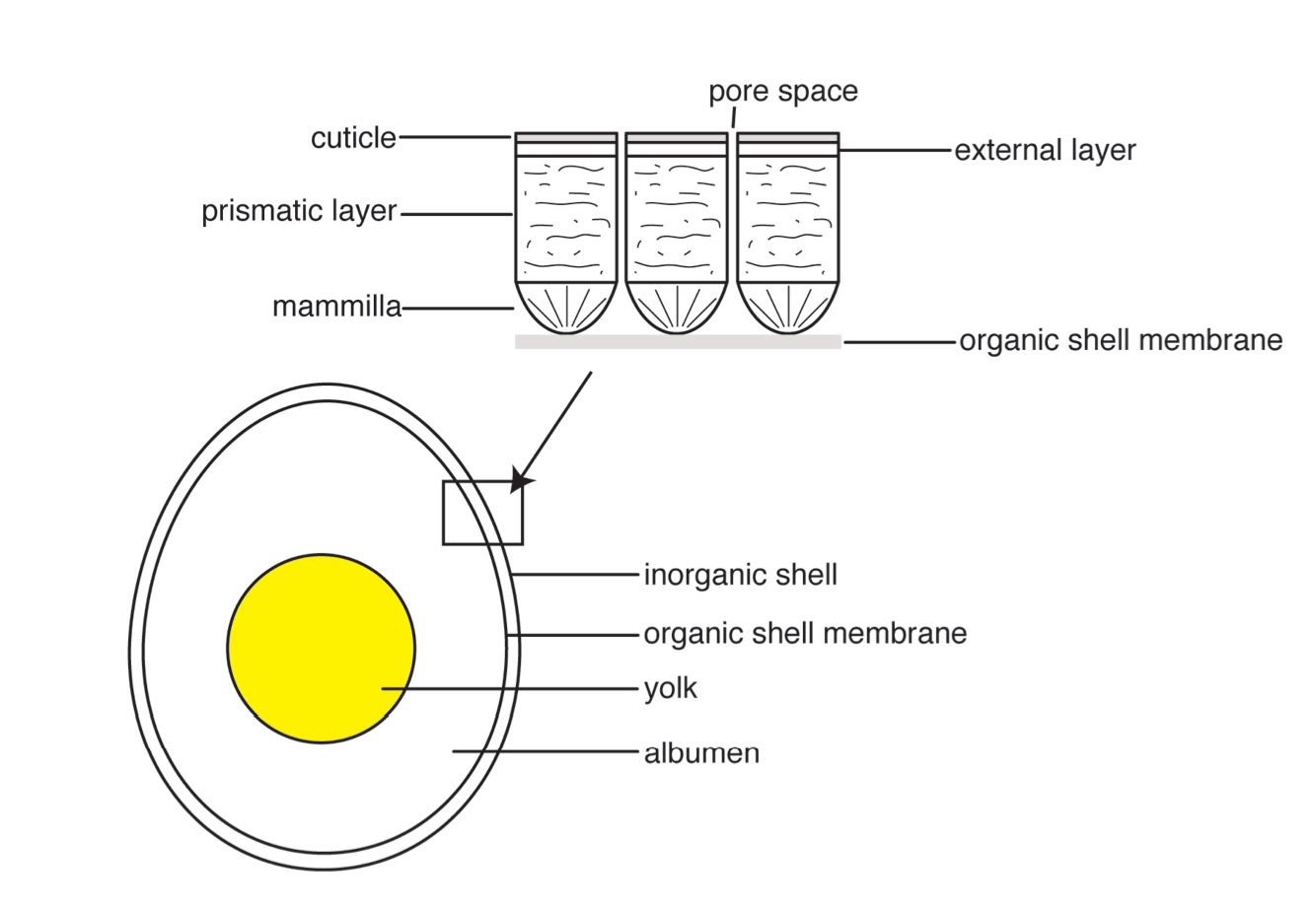

Reptile and bird eggs are composed in a similar basic fashion. The egg consists of yolk, surrounded by albumen, which is contained in an organic shell membrane all held in by a crystalline shell on the outside. The shell is made of calcite crystals in differing arrangements. I will mostly talk about rigid bird and dinosaur eggs because that is what fossilizes the best, but soft, leathery reptile eggs have been known to fossilize too (Hou et al. 2010). Bird eggshells (and fossilized non-avian dinosaur eggshells) are composed of columnar calcite crystals with an organic matrix of collagen fibers. The inner surface of the calcite shell has radiating cones (called mammillae) that are anchored at their tip to a thin organic membrane that encases the yolk and albumen.

Eggshell pores are present along calcite crystal boundaries that provide a mechanism for gas exchange while the eggs are incubating. The sizes of these pores can help us understand paleoenvironments and behavior. For example, a 2008 study of fossil egg porosity by Jackson et al. indicates sauropods did not fully bury their eggs, which gives us a behavioral inference we never would have known before.

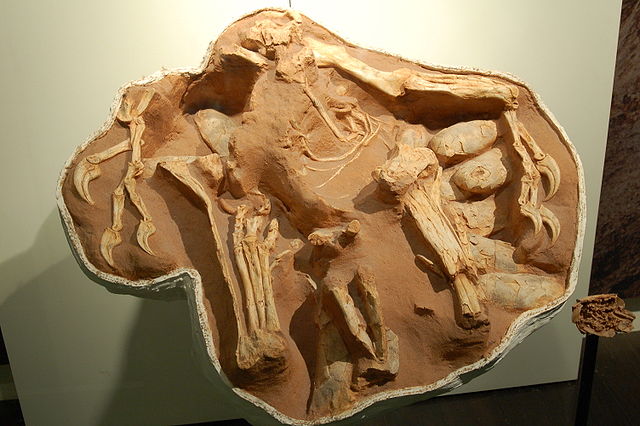

Fossilized bird and non-avian dinosaur eggs come in all shapes and sizes, from big round soccer ball-like sauropod eggs, to elongated ornamented oviraptorid eggs, to tiny fossil bird eggs that are like robin’s eggs. Most of the time you will find eggshell fragments in areas where fossilized eggs can be found, but if you are lucky you can find whole eggs, or even whole clutches. Most famously a specimen of Citipati osmoslkae was found brooding atop a nest of eggs in Ukhaa Tolgod, Mongolia, which helped us learn how dinosaur parents cared for their nests (Varricchio et al. 2008).

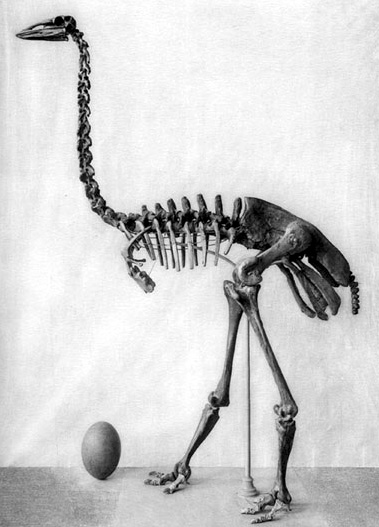

Since eggshells fossilize well and are made of calcite, they can be used for geochemical analyses and paleoenvironmental reconstruction in the same way fossilized tooth enamel can be. Fossil ratite bird eggshells have proved most useful for these sorts of analysis due to the fact they are robust and are present in the fossil record from at least the Neogene to present. Both δ18O and δ13C of extinct elephant bird Aepyornis indicate it ate primarily C3 vegetation in the Holocene landscape of Madagascar, and also had a δ18O less influenced by evaporation than modern ostriches (Clarke et al. 2006). This allows us to better understand potential environmental mechanisms that could have caused the extinction of this species.

Carbon isotopic composition of Adélie penguin (Pygocelis adeliae) eggshells illustrated a recent shift to lower trophic level prey in the last 200 years when compared with the previous 38,000 years (Emslie and Patterson 2007). For a small plug of some of my own dissertation work, dinosaur eggshells from Late Cretaceous Gobi Desert localities indicate clear variation in the paleoenvironments within one region during the same time slice (Montanari et al. 2013). These are just a few examples of how geochemistry can be used to understand ancient environments in great detail using just fossilized eggshell as a proxy, and there are many more excellent studies in the literature.

This is just a small seasonal introduction on something near and dear to me, so I hope you’ve enjoyed it and decided to forgo the Cadbury mini eggs this season for a solid chocolate Citipati one (can someone make me one of those actually?)

References