Madagascar’s Lonely Little Thief

When we think of Madagascar, its unique wildlife immediately springs to mind. Around 95 percent of the terrestrial animals on this island are endemic, meaning that they are found nowhere else on earth. This unusual situation is a product of Madagascar’s isolation, because it is separated from eastern Africa by 250 miles of inhospitable saltwater. That makes it pretty tough for animals to get from point A to point B, and is why you don’t see lions Madagascar or lemurs in Mozambique. For decades, scientists have been working to understand how Madagascar’s unique fauna developed and changed over time. Detailed analyses of modern organisms have certainly been important, but my personal interest is in what the fossil record can tell us. Today, fellow paleontologist Joe Sertich and I published a new addition to this fossil record–a “little” carnivorous dinosaur that predates the next youngest named dinosaurs of Madagascar by around 20 million years.

Madagascar has been isolated for the past 88 million years; for a good stretch of time before that, its only direct connection was to India. The two landmasses formed a single big island in the middle of the Indian Ocean, after they split from Antarctica around 100 million years ago. Somewhat counter-intuitively, it’s been at least 130 million years since Africa and Madagascar last touched! Thanks to a series of stunning discoveries in northwestern Madagascar, we now have an excellent record of life on the island around 70 million years ago. These fossils, unsurprisingly, show close relationships between the dinosaurs of Madagascar and India, with a somewhat more distant link to the dinosaurs of South America (explained by the connection of all of these and Africa via Antarctica, when the continents were closer together).

Despite the excellent 70 million year old fossils, we knew almost nothing about dinosaurs in Madagascar between that time and 165 million years ago. Some fragmentary bones offered a little information, but there wasn’t anything published that could be identified at the species level. This massive gap makes it difficult to document the evolution of Madagascar’s dinosaurs. So, I set out in 2007 to try and change this.

My target was some Cretaceous-aged rocks (from the time period between 145 and 66 million years ago) in northernmost Madagascar. Geological maps and publications indicated that sedimentary rocks from terrestrial environments were exposed in the area, and none of them had been explored for dinosaurs. I used Google Earth to narrow the search region (excluding forested areas and farm fields), scrounged up some grant money, and piggybacked on an expedition from Stony Brook University (my graduate institution) that was already headed to another part of Madagascar. With a small team, I headed up to the area around Antsiranana (Diego-Suarez), a city at the very tip-top of the island. The weather was quite nice thanks to a beautiful ocean breeze, but much of the land was covered in secondary growth following recent deforestation. Virtually every plant was thorny, spiky, pokey, or generally unpleasant; my favorite field hat and a t-shirt or two were ripped to pieces. We searched in vain for days, a discouraging pursuit if there ever was one.

Finally, just a few days before we planned to depart the area, Joe Sertich found some bone poking out of a cliff. It looked to be a vertebra of some sort…and a little digging revealed more bones! The hollow spaces the bones inside made it clear they were some sort of dinosaur. This was a pretty happy moment, because we knew that dinosaur vertebrae can be exceptionally useful for identifying species. We collected all that we could, and Joe returned with our colleague Liva Ratsimbaholison to collect the rest in 2010. Preparators at Stony Brook University carefully removed the rock from the bones, and before we knew it they were ready for study.

We had seven vertebrae and a few ribs. This may not seem like much, but it was more than enough to nail down the type of dinosaur. The arches, hollows, and spines on the vertebrae marked the animal as an abelisauroid–a type of carnivorous dinosaur common to the southern continents during the Cretaceous. Additional comparison revealed many features that were unique to the animal, allowing us to name a new genus and species. Careful examination of the local geology allowed us to estimate the age of the animal with some precision; this was absolutely critical to place it into a broader context.

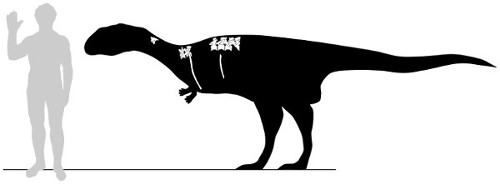

Dahalokely tokana lived about 90 million years ago, and was around 10 or 12 feet in total body length. At this juncture in time, Madagascar and India were still conjoined. This is interesting, because Dahalokely shares features with later abelisauroids known in both Madagascar and India. It could potentially be ancestral to animals from these areas–something I strongly suspect, but which couldn’t be definitively supported in our evolutionary analysis. More bones are needed to nail this down for sure. Regardless, Dahalokely is the first dinosaur to be described from a critical interval in Madagascar’s history, and will undoubtedly figure in future work in this area. It also shortens the “barren” zone of Madagascar’s named dinosaur record by about 20 million years.

So, what’s with the unusual name? As is common for new animals named from Madagascar, we chose to work from the Malagasy language rather than the “traditional” (and Euro-centric) Greek or Latin. A “dahalo” is a thief–most often a cattle rustler. We chose this part because our dinosaur was almost certainly a predator (at least from what we know of its close relatives). “Kely” means “little”, because the dinosaur was certainly on the small end of things, even for an abelisauroid. Finally, “tokana” means lonely–and this dinosaur would indeed have been lonely, way out there in the middle of the Indian Ocean with no way to get off the island!

Dahalokely appears in today’s batch of PLOS ONE articles, where we comprehensively describe, illustrate, and compare the animal. After 90 million years, Dahalokely walks the earth again!

Citation

Farke, A. A., and J. J. W. Sertich. 2013. An abelisauroid theropod dinosaur from the Turonian of Madagascar. PLOS ONE 8(4). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062047

Full disclosure: Although I am a volunteer editor for PLOS ONE and a blogger at PLOS Blogs, I had no role in the editorial process related to my paper.