Prehistoric Platypus: Revenge of the Monotremes

(I tried to make the title of the post sound like a SyFy movie title, let me know how I did)

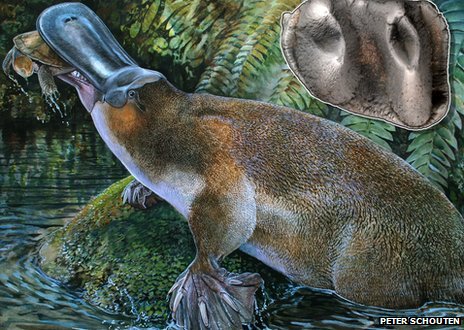

Obdurodon tharalkooschild is not your garden-variety platypus.

Today, the platypus is one of two remaining varieties of living monotreme (the other being echidnas). I could go on and on about the platypus- it does too many cool things to mention them all. Ok, ok, I will name one. The male platypus both has pointy ankle spurs that contain venom (females have the spur, but no venom). This venom isn’t fatal to humans, but is, of course, extremely painful. How is this known? Well apparently a guy wanted to test it out by getting stabbed in the hand by a platypus in the early 90s (paper here) and it really, really hurt. Additionally, “significant functional impairment of the hand persisted for three months”. So no need to try that at home people.

We don’t know if O. tharalkooschild was venomous, but we know that it was huge! This new species is described on the basis of one singular tooth. The beautiful part about mammalian teeth is that even one tooth can be so different than any other known specimen and it diagnoses an entire species. When then-Honors student Rebecca Pian (now a PhD student at Columbia University/AMNH) was looking through the vast amount of fossil material from Riversleigh, she adeptly noticed that this monotreme tooth was not like the others. The tooth in question is a lower first molar, and based on its size, O. tharalkooschild was at least two times larger than its modern counter part Ornithorhyncus anatinus! An adult male platypus is ~50cm long, so O. tharalkooschild was at least 1 meter long!

Riversleigh, the fossil locality this specimen was discovered at, is a famous World Heritage site in the outback of Queensland, Australia. Some of the most spectacular fossil marsupials and monotremes that define the evolutionary history of Oz’s most iconic animals have been found here. Previously, the only fossil platypus known from Riversleigh was Obdurodon dicksoni and all vaguely platypus-y material was referred to that species.

The variation in morphology of this tooth really shakes things up in the world of monotreme relationships. All of the platypus relatives had very similar looking molars, indicating the evolutionary history of these animals was fairly simple. This big ol’ platypus throws a wrench in things—it is lacking twin lophs (ridges) on a certain part of the tooth, which indicates this is a separate radiation from the previously discovered modern and fossil platypuses.

The age of this specimen is a bit vague, based on current stratigraphic knowledge it could be middle Miocene (~15 Ma) or as young as Pliocene (~5 Ma). Either way, it is still an extremely unique specimen that changes what we know about fossil monotremes. The oldest fossil monotremes include animals like Steropodon and Kollikodon, both Cretaceous (~100 Ma) in age, from the Lightning Ridge locality in New South Wales, Australia. Besides being some of the oldest known monotremes, these specimens are unique because most of the fossils at Lightning Ridge are opalised—meaning the minerals in the bones and teeth have been replaced with shiny opal.

Besides the fossils I’ve mentioned, there are a few other fossil monotremes, but the record is relatively sparse. The origin of these animals is still a mystery, although the presence of yet another platypus relative fossil in Argentina (Paleocene in age) gives the indication there was, at one point, a Gondwanan distribution of these enigmatic creatures. Rebecca says “Other than the Patagonian platypus Monotrematum sudamericanum, we have nothing in between the early Cretaceous and the late Oligocene. No fossils have be found from Antarctica either despite evidence that they should be there.” There are a few fossil localities in Australia that seem promising for the discovery of monotreme teeth, so hopefully the record will be filled in in the coming years.

(This research is from an article in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology that is not yet available online)