How much did that dead bird weigh?

“How heavy was it?” Body mass is not just an intuitive way to compare the size of animals, but it’s also critical for understanding their biology. Numerous scientifically interesting attributes can be related to body mass, such as growth rate, bone strength, and even metabolism. If we want to know if an animal grew unusually quickly or slowly, for instance, we probably want to compare it to animals of the same size. In order to fully understand these sorts of features on broad evolutionary scales, it would be really great to estimate body masses for extinct organisms. But, it’s difficult enough to get a live critter on a scale–so can we even hope to learn something about a dead critter known only from bones?

Thankfully, bone size is correlated with body mass. For decades now, scientists have developed methods to estimate mass from simple bone measurements. All it takes is a bunch of bones from animals of known body mass, and then you can write an equation that lets you plug in a bone measurement on one end and get an estimate of body mass out the other end.

The next question is: which bones should you study? An individual skeleton may have dozens or hundreds of bones to choose from, but not every bone will produce a good estimate. Ideally, you want a bone that is weight-bearing. For instance, in humans and other bipedal animals, much of our weight is transmitted through the femur (thigh bone), so you would expect a rather direct relationship between femur dimensions and body mass. Bones that aren’t weight bearing, such as ribs or tail vertebrae, may not produce as accurate of estimates. (Mammalian paleontologists often use teeth because they’re pretty common, but the connection between tooth size and body mass is a complicated one.) Even then, not every part of every limb bone will produce equally accurate body mass estimates, depending on the style of locomotion that an animal uses. Scientists usually use the circumferences of the middles of the shafts on the femur and/or the humerus, the two main weight-bearing bones in most terrestrial vertebrates.

In an ideal world, we would have “One Equation to rule them all” (apologies to Tolkien), but this may not produce the most accurate results. Different groups of animals have different limb bone shapes, and they all hold their limbs slightly differently. An equation that works well for mice may not work well for horses. It makes sense, then, that the best results might be achieved by tailoring equations to specific bones on specific groups of animals.

Daniel Field and his colleagues at Yale University wanted to calculate accurate body mass estimates from the often fragmentary bones of extinct birds. Although previous researchers had taken a stab at this, the samples in many of these studies were sometimes small and almost always only focused on a handful of measurements across the skeleton. Thus, Field and crew were interested in two particular questions: 1) Which bony measurement could best estimate a bird’s body mass? and 2) What was the range of uncertainty on this estimate?

First, the researchers needed to figure out how to accurately estimate body mass in modern birds of known body mass. They measured 863 skeletons representing 317 different species of volant (flight-capable) birds in the collections of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. With 13 measurements on each individual skeleton from the femur (thigh), tibiotarsus (shin), arm (humerus), shoulder (coracoid), and foot (tarsometatarsus) bones, that’s a huge amount of work–over 11,000 individual measurements! Body mass data, which were not always collected for the individual animals that provided the museum skeletons, were taken from the literature.

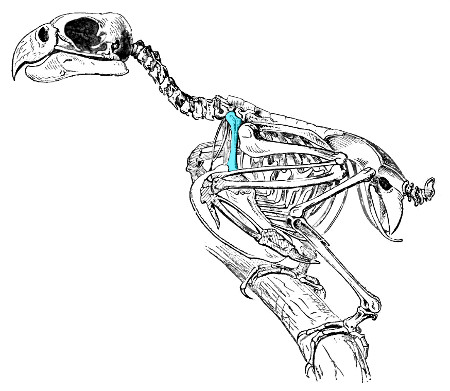

The researchers calculated statistics that evaluated the relationship between a particular measurement and body mass, and found that one measurement in particular worked better than all of the others. One of the shoulder bones, the coracoid (we humans lost a separate coracoid along the way) has a facet where the arm bone (humerus) attaches. The maximum dimension of this facet predicted body mass better than any other measurement in most of the birds that Field and colleagues looked at (in a few groups, the length of the overall coracoid was a slightly better predictor). Not only did facet length produce an accurate estimate–which many other bones did too–but it produced a tightly constrained estimate. Every time you estimate something from a bone measurement, there is a range of uncertainty. This range was tighter for the coracoid facet measurements than any other measurements. Accurate and precise!

Initially, it is somewhat surprising that part of the shoulder joint would be the best predictor of body mass in birds–after all, when they walk around, they walk around on their hind legs. Field and colleagues speculate that this relationship is due to the needs of flight–you don’t want your shoulder joint to fail when flapping your wings, so it makes sense that large birds would have large shoulder joints, and vice versa.

When it comes to fossil birds, it is very convenient that the coracoid is a good predictor of body mass. Coracoids are one of the more robust bones in the bird skeleton, and the part that contributes to the shoulder joint is one of the more commonly preserved pieces in the fragmentary fossil record of birds. Even when the coracoid is missing, there are now a whole bunch of well-tested equations that can be used on other bones. The work by Field and colleagues means that it will be much, much easier for paleontologists to reliably estimate body mass in a variety of bird fossils.

As an added bonus, the researchers published all of the data they used in their study! This means that anyone will be able to run their own analyses (it would be interesting to see if phylogeny is indeed a minor issue as posited by the authors), add additional specimens, or virtually anything else imaginable.

Coming up next…a Q&A with Daniel Field about the paper!

To learn more, check out Daniel Field’s web page or read the full paper over at PLoS ONE. Nic Campione and colleagues also recently published an open access paper on body mass estimation in terrestrial quadrupeds, which also is worth a read.

Citation

Field DJ, Lynner C, Brown C, Darroch SAF (2013) Skeletal correlates for body mass estimation in modern and fossil flying birds. PLoS ONE 8(11): e82000. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0082000