Thrills and Uncertainties: Discovering a New Dinosaur in Madagascar

“$%@# rain. It was sprinkling last night when I went to bed, and [it] was full-scale rain by 3 [a.m.] or so. Still raining at 7. Off and on rain, up to 9 a.m. as I write this. This is the most rain we’ve ever had in the history of the Mahajanga Basin Project.” — Field notes, 19 July 2005, Andrew A. Farke

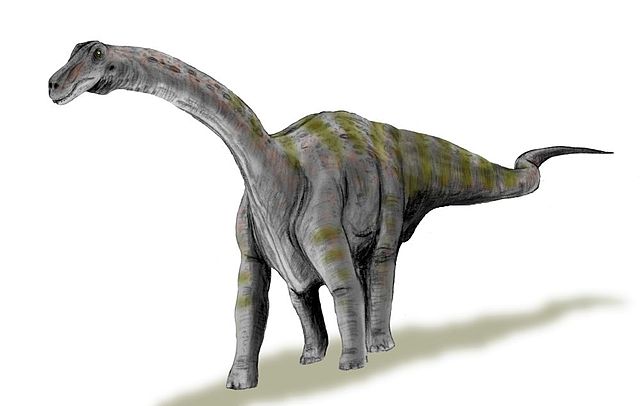

Earlier this week, a mysterious dinosaur from the island of Madagascar finally received a name. Vahiny depereti — meaning “Depéret’s traveler” — designates a species of long-necked sauropod that roamed northwestern Madagascar around 70 million years ago. As a dinosaur fan, I of course love learning all about the latest discoveries. This one is particularly special for me, though. Way back in 2005, I found the piece of skull (a braincase, the part enclosing the brain) that allowed paleontologists Kristi Curry Rogers and Jeff Wilson to pin a name on the new species. When I learned about its publication, I pulled out my field notes to relive the story of that discovery.

“Into the field by 1:45…Robin [Whatley] & I went out to GPS–hit our first site around 2:15. We found that the ox cart road, just starting past the first bridge towards Mahajanga after camp, is an exceedingly efficient way to achieve insertion into the field area…We hit sites 99-43 & 99-43 near, amid some drizzle….After this, we ended up @ 96-07.”

The original specimen for a species, known scientifically as the “holotype,” is the standard upon which all comparisons are based. If the holotype later turns out to be insufficient to distinguish one species from another, the species name can be sunk. Even if a more complete specimen is found later, the holotype is still essential for defining the species. Not much more than 1,000 species of dinosaurs have been named, so the set of people who have found a holotype is pretty small. As a little kid nuts about dinosaurs, and even as a graduate student, I dreamed of joining that elite club. I of course have been lucky to be involved with naming several species, which was a tremendous privilege in its own right, and helped collect a holotype or two, but never before have I actually been the human who first laid eyes on the specimen.

“This site shows some real potential–maybe it’s the multi-taxon bonebed Dave [Krause] wanted? I found a braincase-looking thing which I soaked with consolidant. That, or it’s a vert [vertebra] chunk. It started to pour rain ~4:15, so we had to ‘abandon ship.'”

When a fossil is discovered in the field, it is usually covered in rock. As a result, a confident identification can be quite difficult. What is thought to be a flying reptile turns out to be a crocodile, or what is thought to be a fish jaw turns out to be a bird bone. In the rocks of the Maevarano Formation, where Vahiny (pronounced “va-heenh”) was discovered, sauropod bones are ridiculously common. This is great if you want to learn about sauropods (and who doesn’t?), but can be problematic when trying to make field identifications. The insides of many sauropod vertebrae are riddled with complex empty spaces, where air sacs once resided. When a vertebra weathers out, the interesting shapes on the fragments can fool even a trained eye into seeing a dinosaur skull piece, bird limb bone, or other find of great importance. During my years in Madagascar, I quickly learned to temper expectations for a freshly discovered bone.

“The braincase / sauropod vert frag is a braincase after all. Basioccipitals are distinct, & I found an occipital condyle which fits on nicely. The specimen is a little weathered, being on the flat, but should prep out nicely. The rostral end is heading down into the ground, but the dorsal bit seems a little gone. I would really like it to be sauropod. But maybe croc?”— Field notes, 21 July 2005, Andrew A. Farke

A rounded knob of loose bone that fit onto the mystery fossil confirmed its identity as a braincase–the part of the skull that encloses the brain and connects to the neck. Even once you figure out what bone is exposed, obscuring rock still makes it tough to determine the kind of animal that the bone came from. On top of that, paleontologists are always learning new anatomy. When I found the skull bone of Vahiny, I had some experience with crocodile braincases, and horned dinosaur braincases, and a few other types of braincases, but not much with sauropods. I also knew that sauropod skull bones are pretty rare. The tiny heads perched on the end of the long neck don’t fossilize well, compared to the robust limb bones or even the somewhat delicate vertebrae. I really, really wanted my discovery to be part of a sauropod skull–but, I knew based on what else we had been finding nearby that part of a crocodilian skull was far more likely.

“I collected loose frags of the braincase in a small bag. Jacketed it in a specialist; perhaps a good specimen to CT before prepping? Esp. if it is sauropod (I can always hope!)”

Once a fossil is exposed in the field, it has to be carefully packaged in order to survive the trip back to the lab. Durable jackets, made from cloth strips soaked in plaster of paris, cradle the fossil and its surrounding rock just like a broken arm in a cast.

After the end of the 2005 field season, the mysterious fossil was shipped back to the fossil preparation lab at Stony Brook University, where technicians Joe Groenke and Virginia Heisey began work. First, they ran the specimen through a CT scanner, to see what was inside–and it turned out to be a sauropod braincase! After weeks of cleaning and stabilization, the fossil was ready for scientific study. Kristi Curry Rogers (an expert on the sauropods of Madagascar) and Jeff Wilson (another expert on sauropod dinosaurs) collaborated to figure out just what kind of sauropod the braincase came from.

I had expected that the braincase came from Rapetosaurus [pronounced “ruh-PAY-too-SAWR-us”]. This animal is well known from several partial skulls, and another braincase would be nice to fill in some details on individual variation. Interesting, but not terribly exciting. So, my jaw dropped when Kristi told me that the bone I found wasn’t Rapetosaurus, but something totally different! Based on other odd bones found in that part of Madagascar, she had long suspected that there was another species of sauropod lurking in the area, but never had evidence good enough to confidently name an animal. Fortunately, sauropod species are readily distinguished by their braincases. The little fossil I found was the key to unlocking the puzzle.

The scientific paper naming Vahiny depereti clocks in at 12 printed pages (sadly, not open access), with a detailed description and copious figures of the fossil. A second specimen, a fragment from the braincase of a juvenile, has also turned up, adding a little more information. Kristi and Jeff showed that the braincase of Vahiny was quite different from that of Rapetosaurus, and in fact was most similar to the fossils of an animal from India called Jainosaurus. This is not terribly surprising, because Madagascar and India were connected until around 88 million years ago, so the dinosaurs from both land masses are fairly similar. Vahiny also showed some resemblances to sauropods from South America, again unsurprising given paleogeography.

For now, only the skull bones can definitively be called Vahiny. As mentioned above, other bones from the same part of Madagascar may also belong to the animal, but it will take an associated skull and skeleton to dispel any doubts. There is always more work to do!

Nearly 10 years after that discovery of an unremarkable looking bone, it has been fun to look over my field notes from those days. During our training as paleontologists, we learn all about the scientific importance of these notes, for recording information on geographic location, rock type, associated fossils, maps, and the like. However, our notes also preserve the highs and lows of a field season, and the thrills and uncertainties associated with any discovery. These emotions and memories are just as much a part of science as the fossils themselves.

“Awoke at 3 a.m. to a sound of guitar music — I guess it was probably a cattle man with the omby [cattle]. Some of the omby wandered through camp in the night…” — Field notes from fieldwork near Lac Kinkony, Madagascar, 5 August 2005, Andrew A. Farke

Citation

Kristina Curry Rogers & Jeffrey A. Wilson (2014) Vahiny depereti, gen. et sp. nov., a new titanosaur (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Maevarano Formation, Madagascar, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 34:3, 606-617, DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2013.822874 [paywall]

The field note excerpts presented here have been edited for style, brevity, and profanity. Thank you to Dave Krause and the other leaders of the Mahajanga Basin Project, for the opportunity to participate in this fieldwork. The MBP is funded by National Science Foundation and National Geographic Society grants to Krause and others.