At the heart of the Open Science movement is the conviction that Open Science is better science. More rigorous. More inclusive. More…

Lungfish brains ain’t boring

I tend to think of fish brains as fairly unremarkable. Too simple relative to mammal brains, too un-dinosaur-y relative to dinosaur brains. Shark and perch brains get a brief nod in many comparative anatomy classes, but mostly to lament how “primitive” they are. Check ’em off the list, make a sketch, pass the quiz, and let’s see how fish brains evolved into something more interesting.

But, I only just learned that my callousness is more than a bit unwarranted. Researchers Alice Clement and Per Ahlberg, both from Uppsala University, Sweden, last week published a fascinating look at the reconstructed brain of a 380 million year old lungfish from Australia, Rhinodipterus. In conjunction with previously published work, a fascinatingly complex picture of lungfish brain evolution emerges.

Lungfish are particularly interesting to study due to their long fossil record–over 400 million years–as well as their key position within vertebrate evolution. Today, there are three main lungfish genera–Neoceratodus (the Australian lungfish), Lepidosiren (South American lungfish), and Protopterus (African lungfish). Only Protopterus has more than one species. Lungfish as a group are probably the fish most closely related to limbed vertebrates (tetrapods, including salamanders, turkeys, and humans, to name a few), and thus are an important reference point for understanding tetrapod evolution.

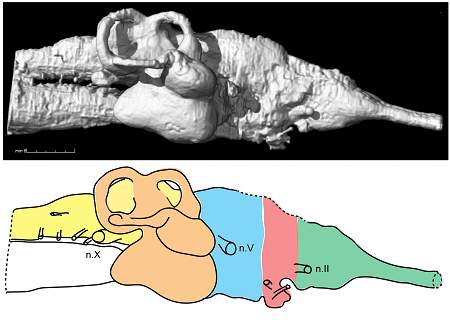

The problems with studying lungfish brains, though, really occupy two levels. The first is that brains don’t generally fossilize well–so, paleontologists have to rely on a “cheat code” to view the brains in extinct animals. Brains are encased in brain cases, a skull structure that often preserves at least the basic contours of the brain. Use a CT scanner to look inside the braincase, make a spinning digital model of the brain. But…the braincase is mostly cartilaginous in modern lungfish as well as many fossil species. Thus, even the basics of brain anatomy are essentially unknowable for much of lungfish evolution.

Thankfully, many early lungfish did have bony skulls. Nonetheless, many of the known fossils were crushed, incomplete, or incompletely studied. We are fortunate to have the fossil resources of the Gogo Formation, a 380 million year old set of rocks that preserves the remains of a marine reef. The specimens from here are spectacular (including an embryonic fish still connected to its umbilical cord), uncrushed, and beautifully freed from their rocky cradles using advanced preparation techniques. One of these fossils included a partial skeleton of the lungfish Rhinodipterus kimberleyensis. The braincase was CT scanned, and then a digital model of the inside contours was created to approximate the brain. This digital model, in turn, was then compared with published data from a few living and a fossil lungfish.

One of the most striking findings is that the reconstructed brain of Rhinodipterus is more similar to that of Neoceratodus, the modern Australian lungfish (picture at end of post), rather than that of the other modern lungfish (i.e., those from Africa and South America, Protopterus and Lepidosiren). Because Neoceratodus and the ancient lungfish Rhinodipterus share this “primitive” shape, Clement and Ahlberg hypothesized that the brain shape of other modern lungfish probably evolved as a unique evolutionary innovation. Other researchers have noted that the brains of today’s amphibians share some similarities with those of Protopterus and Lepidosiren. Looking at the entire evolutionary tree, it is now apparent that this was simply convergent evolution.

Clement and Ahlberg also looked into what brain says about function and behavior. They note that lungfish probably developed an enhanced sense of smell through their evolution, based on changes in the size and shape of the part of the brain associated with olfaction. Some differences in the inner ear–which is related to sensing changes in body position, movement, as well as sound–are also apparent across species, but the specific implications of these differences are a little hazier.

Lungfish brains are surprisingly interesting! My congratulations to the authors on producing a very accessible piece of work. If a dinosaur paleontologist can understand it, that’s an achievement! Yet, even with this new study, there is so much more to learn. Hopefully studies of other well-preserved specimens will provide additional information on the noggins of these fascinating animals.

Citation

Clement AM, Ahlberg PE (2014) The first virtual cranial endocast of a lungfish (Sarcopterygii: Dipnoi). PLOS ONE 9(11): e113898. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0113898