Vampire Giraffe Deer Beasts: What Are Palaeomerycids, Exactly?

If you eat red meat, you’ve probably eaten a ruminant. This group of hoofed mammals includes our domesticated cattle and sheep, as well as deer, giraffes, pronghorn, and more. As a whole, ruminants are best known for their unique digestive system, where the food is chewed, swallowed, digested, regurgitated, and then rechewed (“chewing the cud,” to use a common phrase). Visually, many ruminants are striking for their cool headgear, ranging from antlers in deer to knobs in giraffes to full-on horns in cattle. But, our modern ruminants are just the “left-overs” of a group with a very rich fossil record. Dozens of odd-ball ruminant species have lived over the past 30 million years, many of which are hard to place on the evolutionary tree relative to today’s animals.

One such group is the palaeomerycids, a group of plant-eaters with a truly frightening appearance. Although their bodies were rather deer-like, the skulls of males sprouted vampire-like fangs, a pair of giraffe-like knobs over the eyes (sometimes developed into horns) and a third horn off the back of the head. Palaeomerycids were pretty common throughout Asia and Europe during the Miocene, from around 20 million to 13 million years ago.

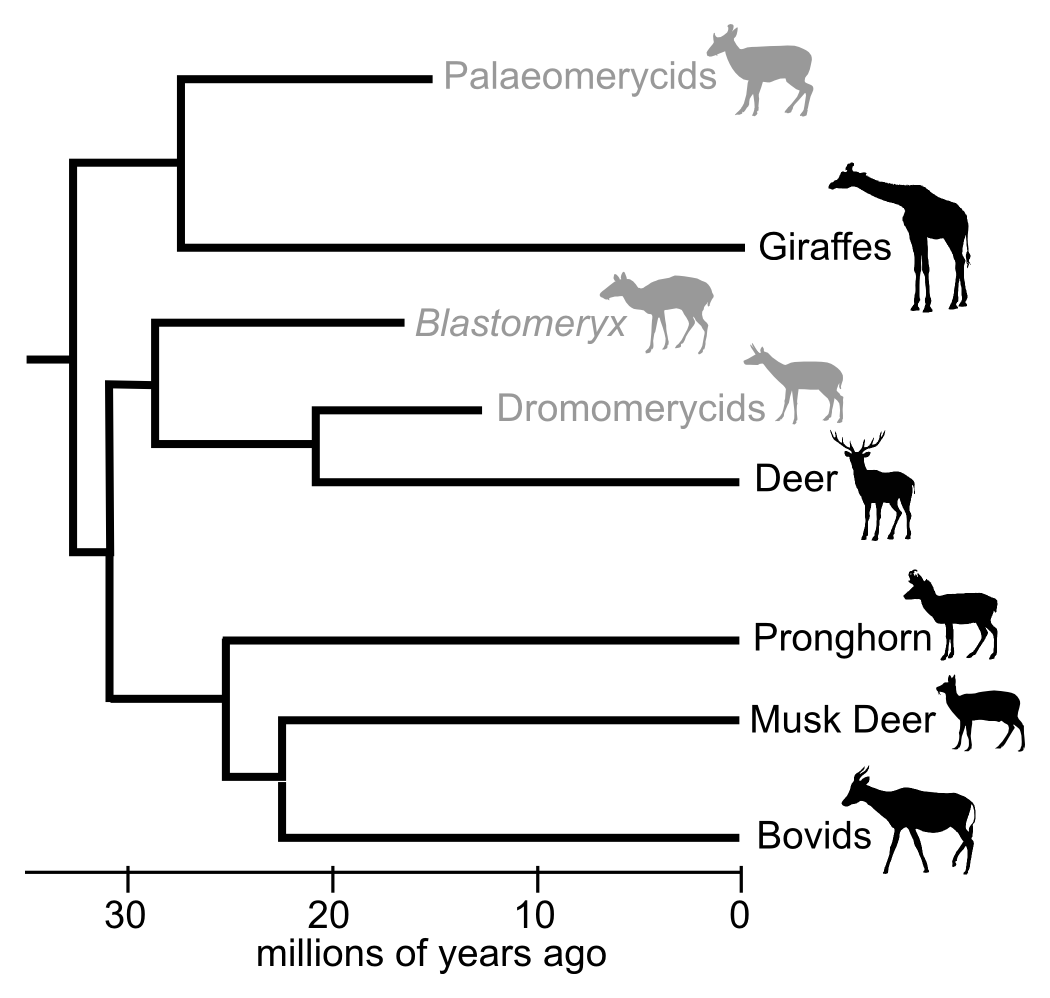

Because of their unusual anatomy, palaeomerycids have been tough to place in the evolutionary tree. Although a number of features in their bones and teeth confidently identify them as ruminants, their closest relatives in this group have been uncertain. Many previous studies have linked them with an extinct group from North America, the dromomerycids. Some dromomerycids are superficially similar to palaeomerycids in having three skull protuberances, but a handful of authors have also suggested this is just evolutionary convergence. Among modern animals, palaeomerycids have been linked most closely with either deer or giraffes.

Research by Israel Sánchez and colleagues, published this week in PLOS ONE, provides a new and detailed analysis of palaeomerycids. The springboard for the study is a new species, Xenokeryx amidalae (pictured above), known from numerous bones found in 16 million year old rocks from central Spain. The name, meaning Amidala’s Strange Horn, refers to the similarity between this ancient animal’s headgear and a hair style worn by Padme Amidala in one of the Star Wars movies (The Phantom Menace, for those who keep track of such things)! Using data from Xenokeryx and other animals, the researchers looked at the evolutionary relationships of palaeomerycids and their close relatives within ruminants.

Overall, the anatomical information suggests that palaeomerycids belong in a group with giraffes and their close relatives, far separated from deer or dromomerycids. Sánchez and co-authors note numerous features of the foot bones, jaw, and skull to support the giraffe/palaeomerycid grouping, and hypothesize that the knobs over the eyes on Xenoceryx and friends is genetically equivalent to the same knobs in giraffes. These are not necessarily new ideas to the literature, although they haven’t been always been as firmly supported. Nonetheless, interpretations of how various horns and knobs evolved remains a topic of vigorous debate, and I suspect that even this paper will not be the final word. Additionally, although giraffes and palaeomerycids now seem to be pretty firmly linked, their joint relationship with other ruminants is still tentative, even in the new analysis. There’s lots of work to do yet!

So, why does all of this matter, beyond collecting information on family trees? Well, their dense fossil record makes ruminants a model group in which to study the evolution and response of life against the backdrop of global change. All of these animals, palaeomerycids included, have lived through major global warming and cooling events, expansions and contractions of grasslands versus forests, and the evolution and extinction of many groups of predators. With a solid ruminant family tree in hand, it becomes much easier to start testing ideas about the forces pushing and pulling their change through time. Additionally, a reliable family tree can help identify “relict” species–those animals that have no other close relatives alive today and which would be a particularly tragic loss of biodiversity if allowed to go extinct. Indeed, past history is crucial for understanding the present and future for many of today’s ruminants, particularly those on the brink of extinction or at the edge of recovery.